The canning of beer started shortly after prohibition ended in 1933.

Food had been successfully canned since a period prior to the mid 1800's.

Two issues delayed the canning of beer- the first being the construction

of a can strong enough to withstand the higher pressures of the carbonated

beverage. The bigger issue was the bad reaction that occurs between

beer and metal. The canning companies worked on this problem throughout

the 1920's and were ready to tap into this huge market once prohibition

ended.

The can companies were met with a great deal of skeptism from the brewers.

Consumers were accustomed to purchasing beer in draft form at their local

taverns and in bottles for home use. The brewers, still reeling financially

from prohibition, had a great deal of cash invested in bottling equipment.

|

|

|

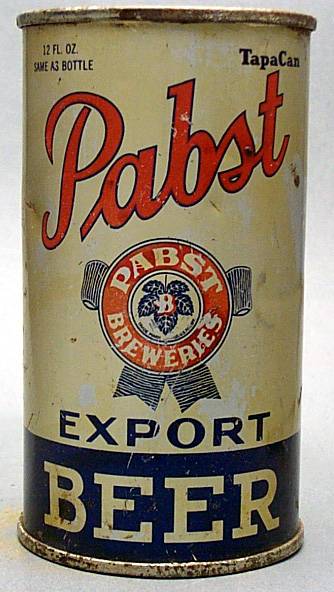

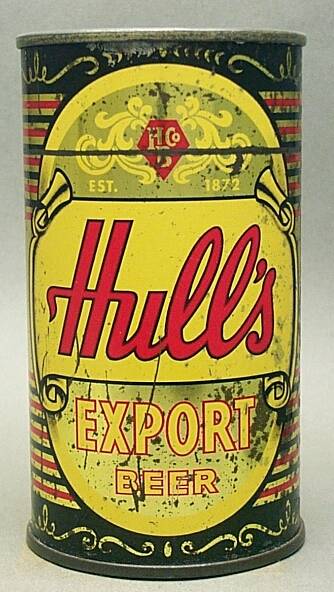

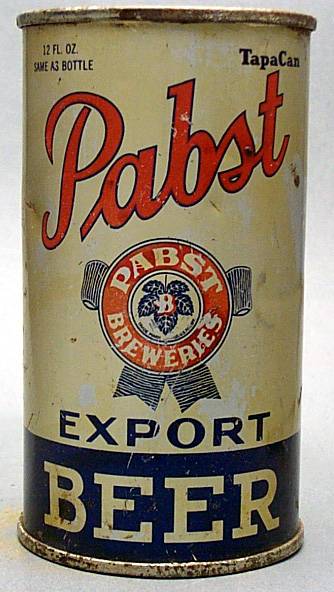

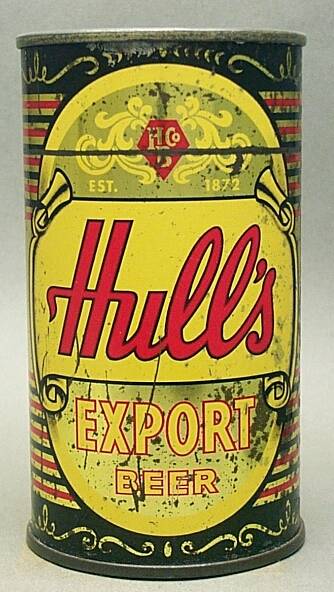

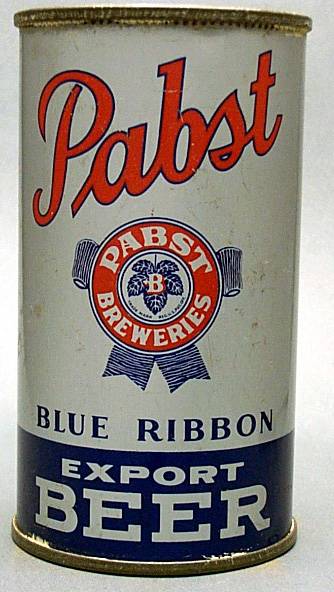

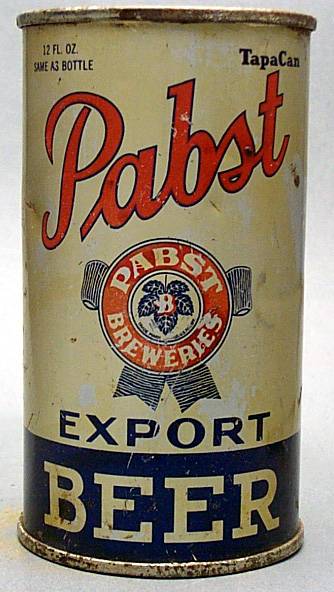

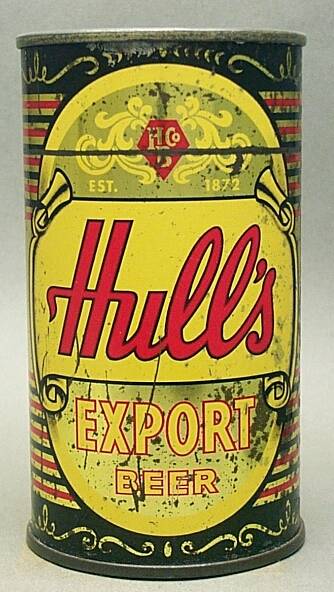

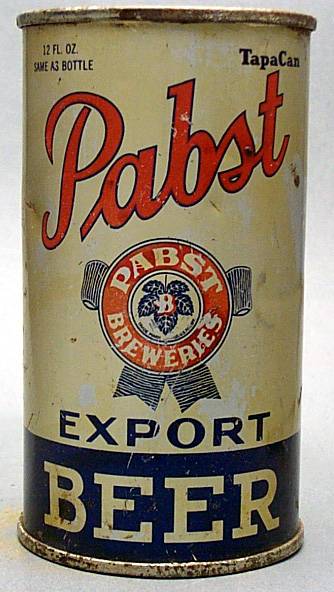

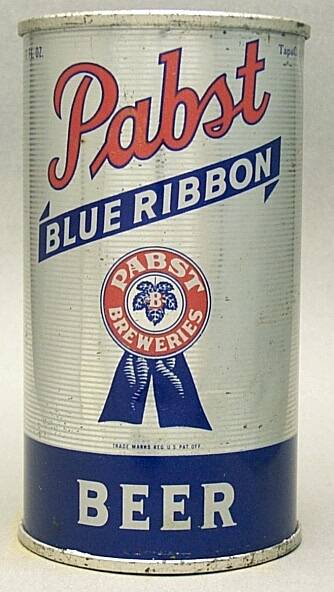

Brewers including Pabst of Milwaukee and Hulls of New Haven,

CT were cautious about cans and often placed only Export versions of their

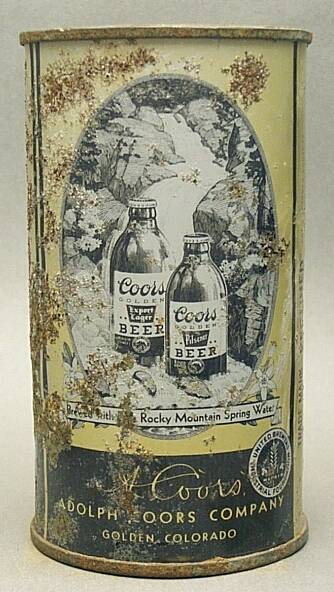

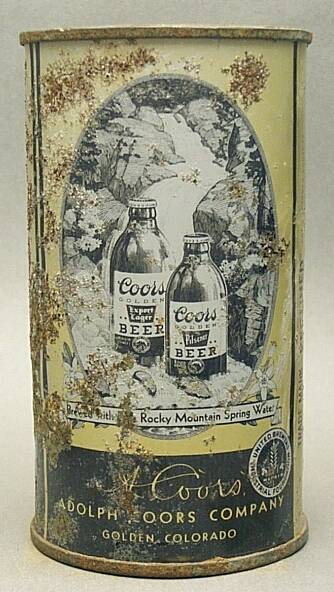

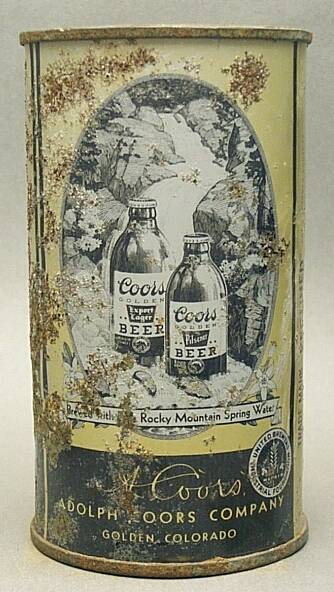

beer in cans. Others such as Coors of Golden, CO reassured

customers with a picture of the familiar bottle.

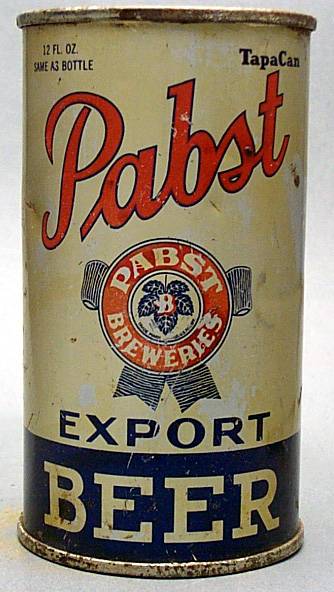

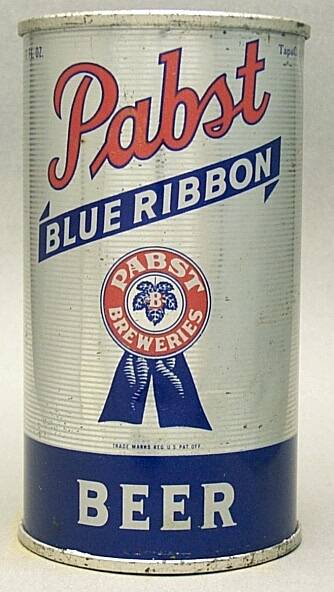

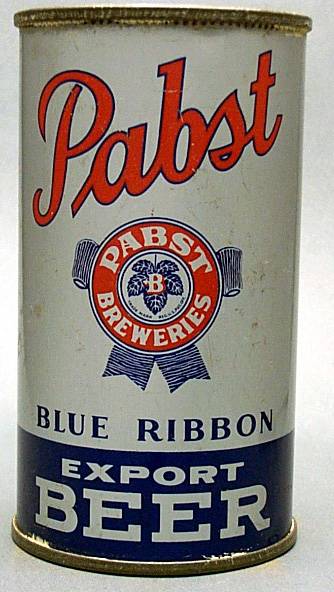

Later on, as seen in the Pabst cans below, the brewers gained confidence in the can an began to package their flagship products in the can.

|

|

|

Brewers including Pabst of Milwaukee gradually moved it's Blue Ribbon into the can.

In late 1933, the Krueger Brewing Company canned what is considered to

be the very first beer- Krueger Special Beer. This likely was a test,

since the company did not begin actively marketing their product in cans

until January of 1935. They proceeded cautiously by by selling a

special ale in Richmond, VA, a city; far from their core market.

The canned beer turned out to be a hit with sales increasing 550% in the

first six months.

By summer time, American Can was able to convince a major brewer, Pabst, to can beer. Pabst,

hesitated to place their flagship Blue Ribbon

brand in cans and instead hedged their bets by canning their Export brand. Both the Pabst and

Krueger look much like today's 12 ounce cans. Many early brewers took Pabst's approach by

placing

what they would call their Export brand in cans.

The can makers tried to assure their

customers of these beer can by printing such phrases such as "12 OZ SAME AS BOTTLE" directly

on the front of the can. Some brewers, such as Coors, even went so far to place a picture of

their bottled products right on the can.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

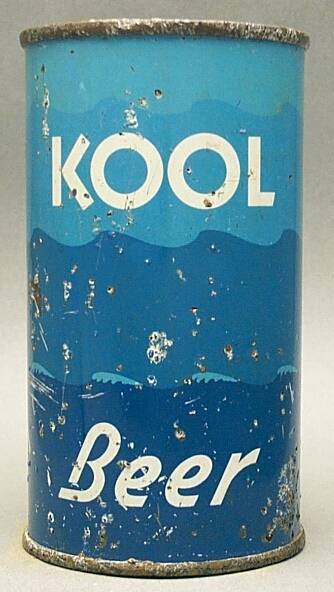

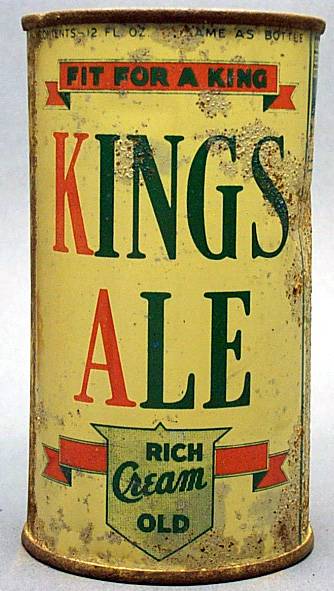

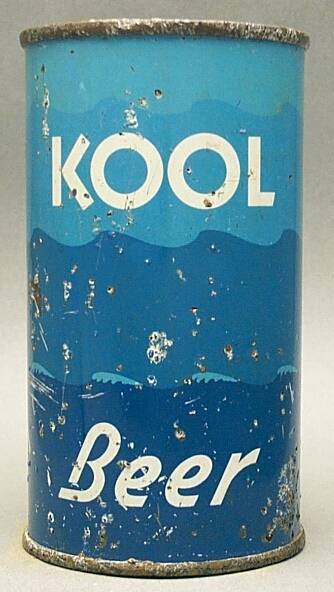

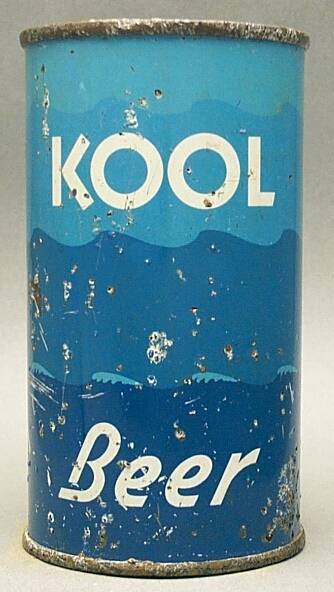

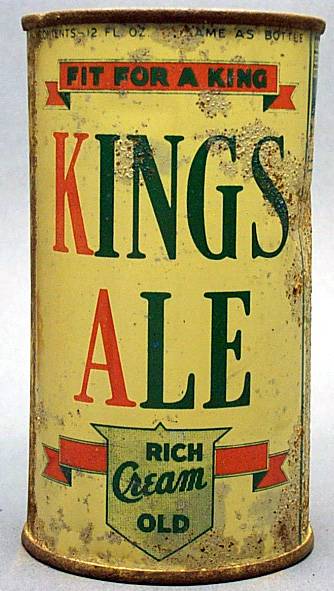

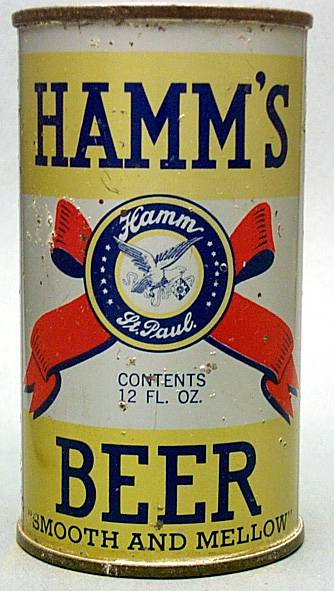

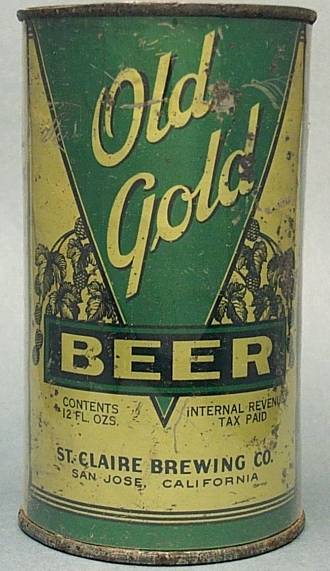

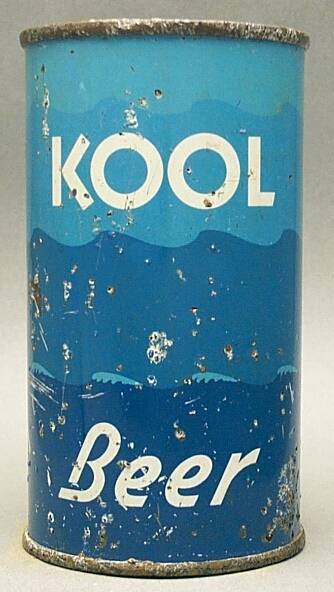

The huge "BEER" and "ALE" on these early cans introduced drinkers to an all new container.

They also had to go out of their way to inform consumers that these new container actually

contained beer or ale. Unlike todays cans, the words "beer" and "ale" were often larger

than the actual brand name. The Kings Ale from Kings brewery of New York City and the

Kool Beer form the Grace Bros. brewery of Santa Rosa, California illustrate this.

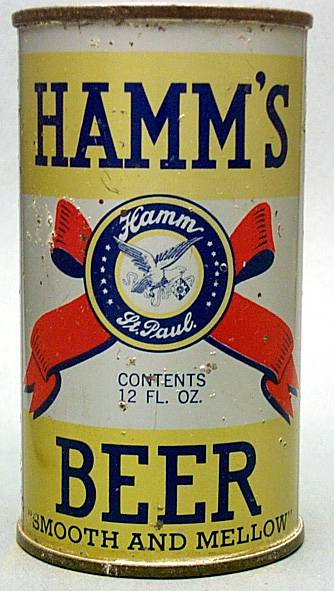

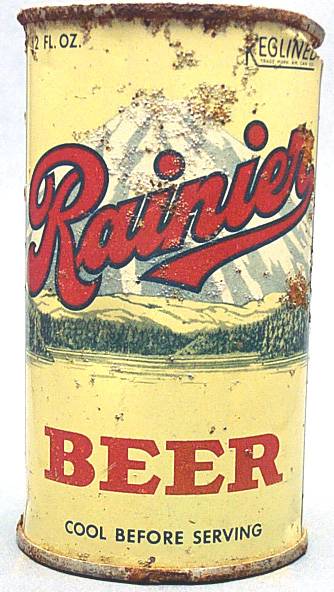

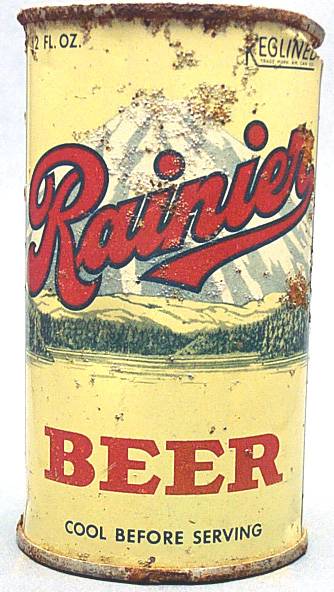

The Hamms

beer from St. Paul, Minnesota and the Rainier beer from Seattle Malting and Brewing

also show this trait common in early beer cans.

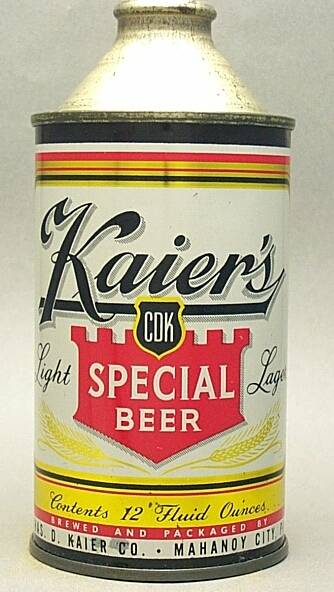

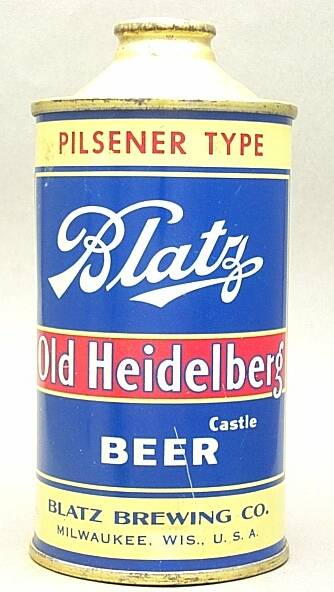

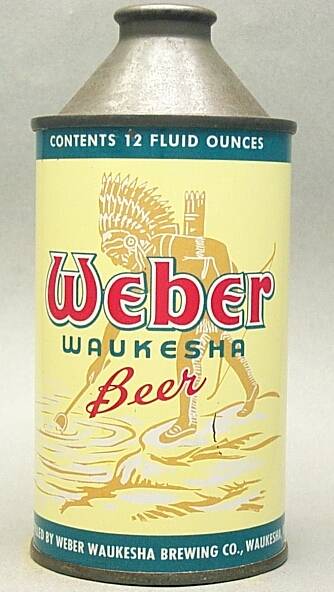

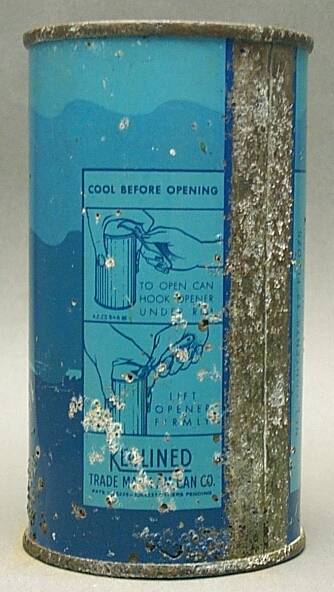

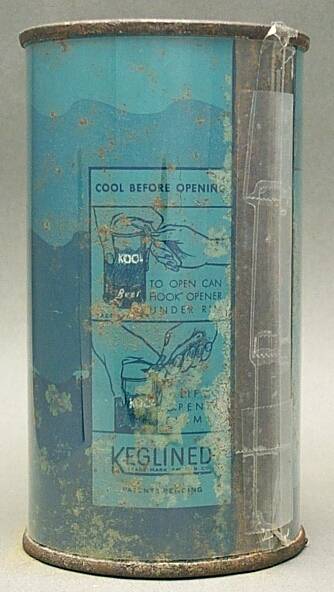

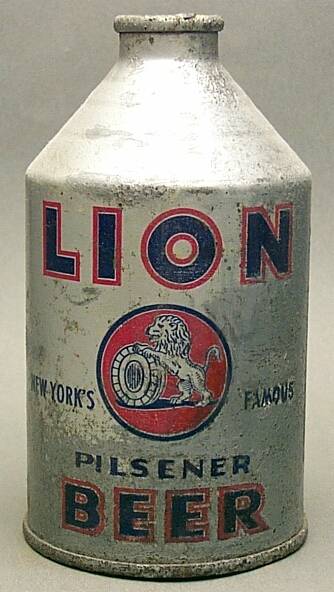

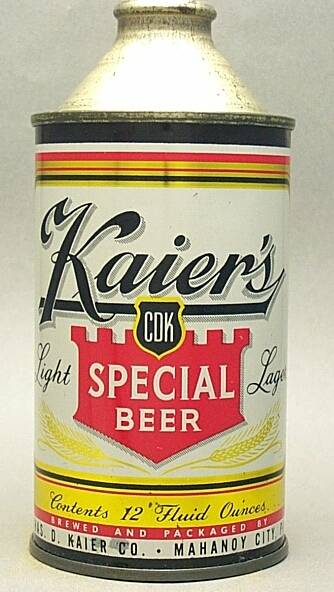

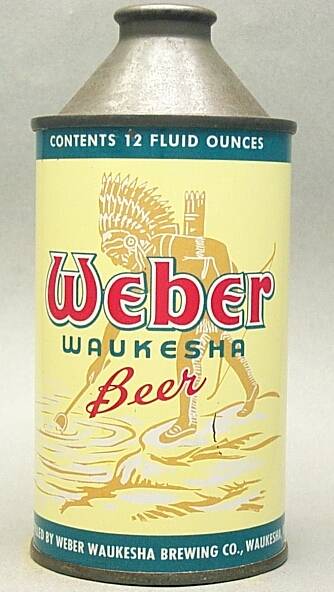

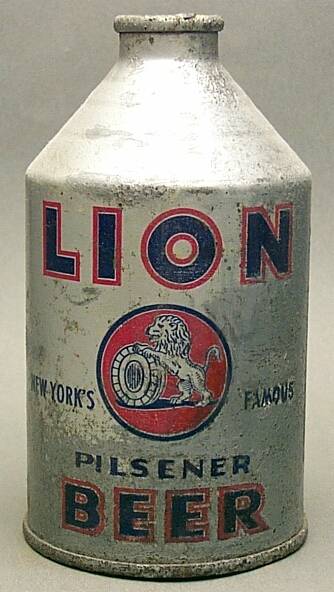

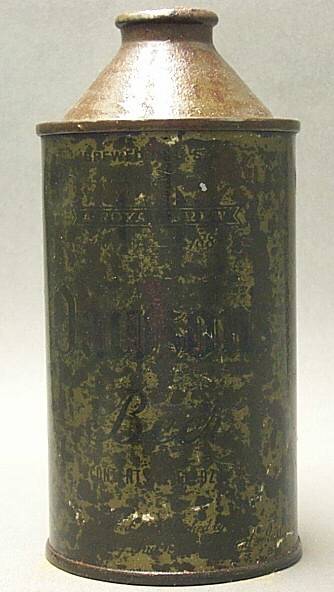

An alternative beer can was introduced by Continental Can at this time. This can,

called a cone-top, more resembles the bottle to which beer drinkers were accustomed.

|

|

|

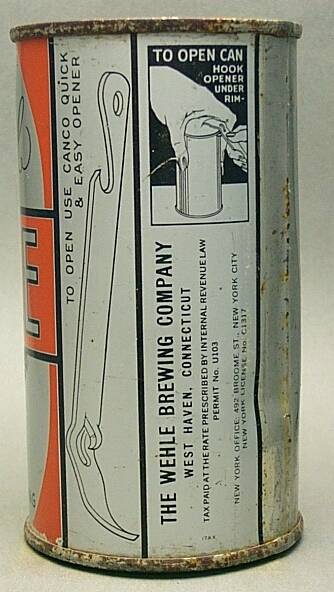

The cone top can could be filled on existing bottling lines and opened just like a bottle

The conetop was capped with a bottle cap and could be filled on the bottling lines already

in place at the breweries. By contrast, brewers had to install new equipment to handle

the new flat top cans. From the consumers point of view, the conetops opened in the

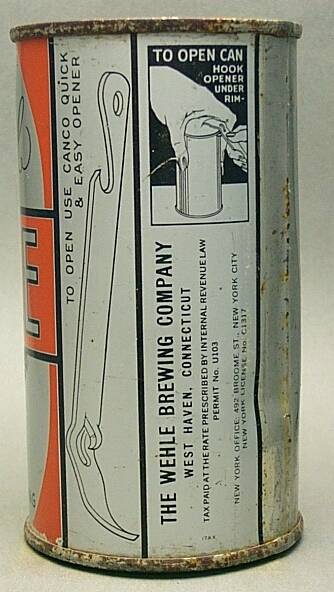

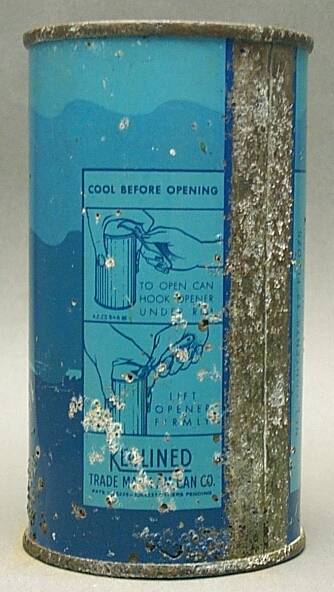

same manner as the traditional bottle. The flat top can required a special opener to

punch a pair of holes in the top of the can. Brewers would give the can operers away with

the purchase of a number of cans and printed opening instructions on the back of the

cans to help beer drinkers get at the goods. The opening instructions on the can are sure

sign of a very old beer can.

|

|

The back of this early Wehle Ale can introduced the can opener to beer drinkers. It also showed how to use it.

|

|

|

There are a couple of different versions of the Kool can opening instructions. One even shows how to open an actual Kool can.

The flat top cans possess the advantage to the

brewers of being faster to fill with beer and more compact to transport. Retailers

can also stack these cans in attractive displays. A visit to the grocers will indicate

which side won this battle. The cone top beer can all but disappeared during the 1950's.

The can makers had a bigger battle to fight. The glass companies were not about to

sit idly by and allow their market to be taken away. They pointed out that beer from a

can had a tin taste. They also noted that because you could not see through a can, one

could never be sure what was inside the can. Of course, the brewers had been selling

their product for years from a barrel. The can companies countered by pointing out that

since the bottles were returned for a refund, one could never be certain what had been

in the bottle. They also pointed out that cans were lighter, easier to transport, and

cooled down more quickly. Some early advertisements illustrated the cans No-deposit, No-return

benefit by showing beer drinkers tossing their empties into a lake. Times change.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Crowntainers were a 2 piece steel can with an aluminum coating.

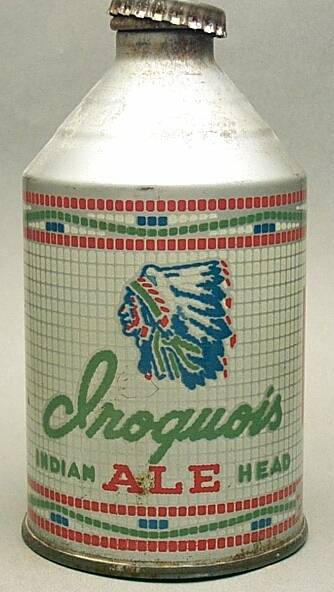

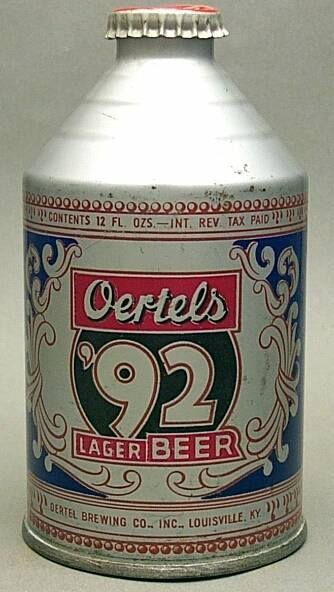

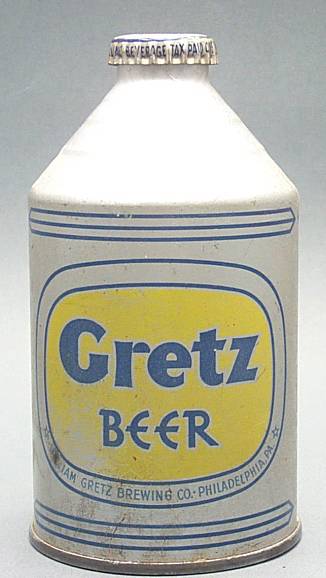

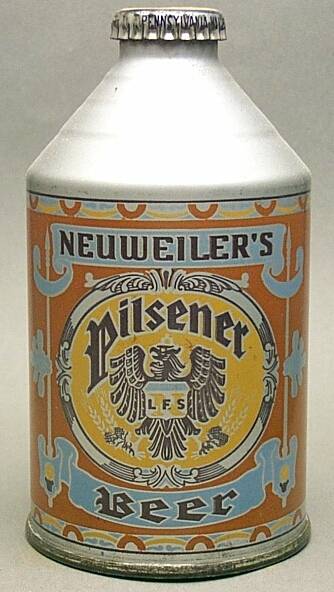

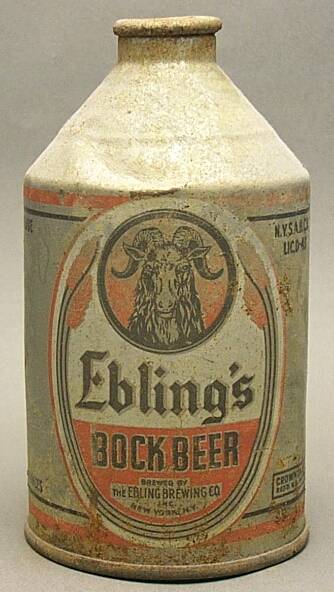

Another entrant in the early beer can battle was the crowntainer by Crown Cork and Seal.

This was a cone top style can with a difference. The old cone top and flat top cans were

three piece cans. The body of each was a flat piece of metal rolled into a cylinder with

a top and bottom added. By contrast, the crowntainer was a two piece can. The body of the

can was drawn into a cylindrical shape with a built-in cone at the top. This can was

make of steel with an aluminum coating. Unfortunately, it is more difficult to apply

quality graphics to a cylinder than to a flat piece of metal. As a result, crowntainers

tended to be less attractive than their competition. Incidently, todays moder aluminum beer

can is made with a similar process with the bottom and side drawn from a single piece of

metal. Graphics on modern beer cans pale in comparison to the three piece cans produced from

the 1930's to around 1980 or so. Most crowntainers had the brewer's logo applied directly

over the aluminum coating. For this reason most crowntainers are the same dull

color. Some

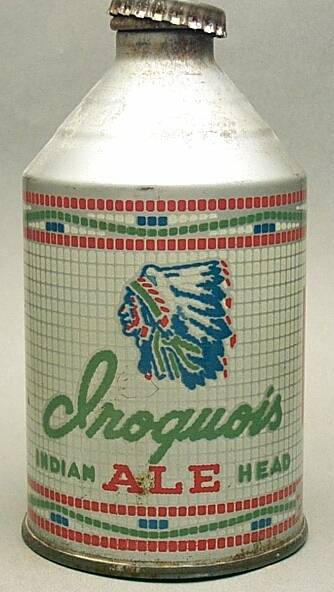

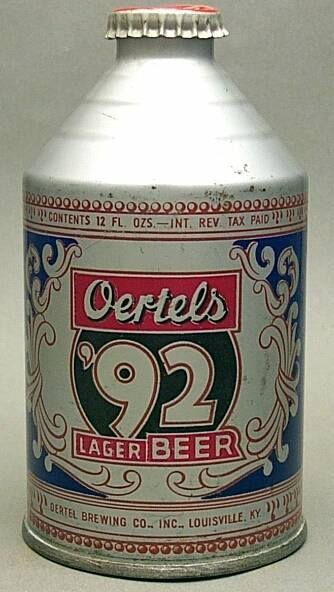

brewers painted the entire crowntainer, resulting in a nicer looking package. Pictured on this

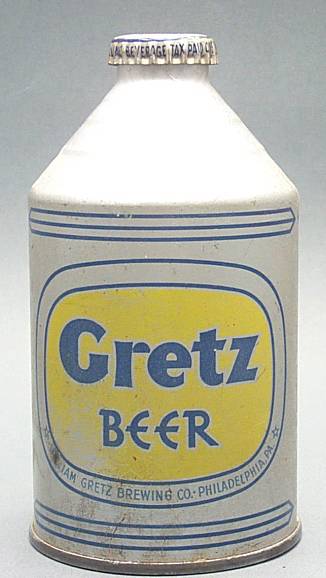

page are the Oertels '92 crowntainer from Oertels of Louisville, Kentucky. The Gretz from Phildelphia is another old crowntainer. Also pictured

the a painted Old Fashioned crowntainer from Northhampton Brewing of Northhampton, PA. The

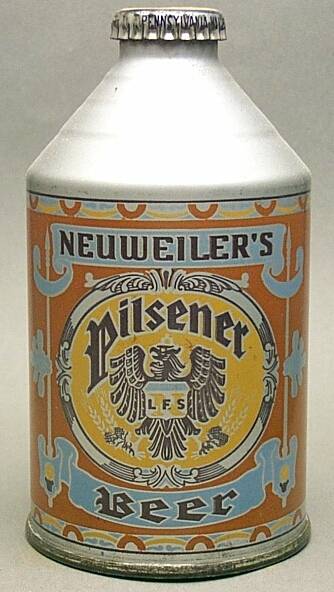

Neuweilers from Allentown, PA has a partially painted label. The

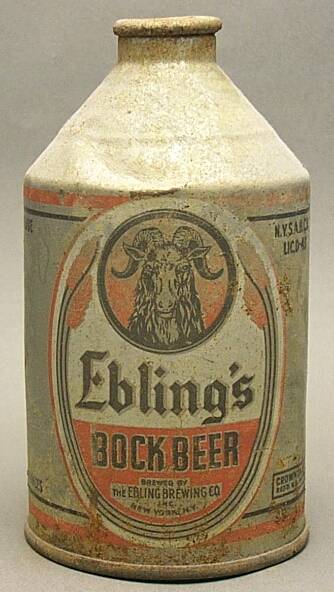

Ebling Bock can from New York City is a rare example of a bock beer style

crowntainer. The Iroquois can is from the brewery of the same name in Buffalo,

New York.

Quart bottles were popular before prohibition. Most preprohibition bottles that are found tend

to be about the size of two modern beers. This was not suprising since in the 19th century

many bottles were still hand blown. Not surprisingly, breweries in the post-prohibition era

packaged their products in quart bottles and looked for a quart can package as well. The

quart cans are especially desirable amongst collectors because they are so strikingly different

from todays beer can.

|

|

|

|

|

|

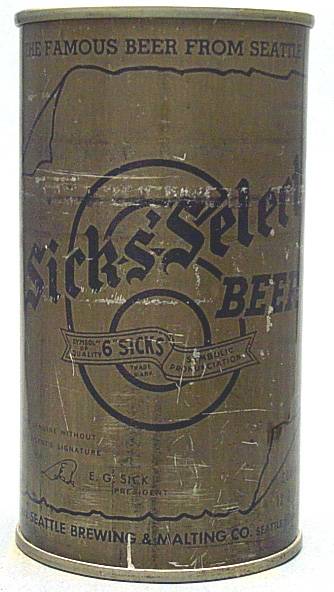

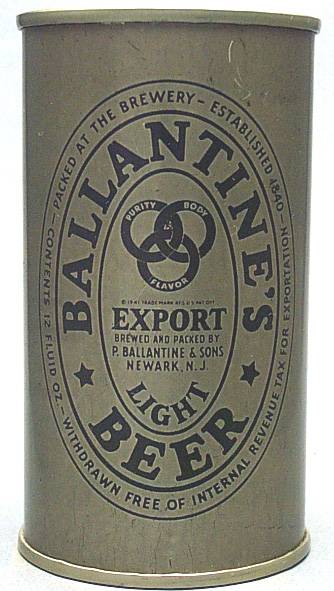

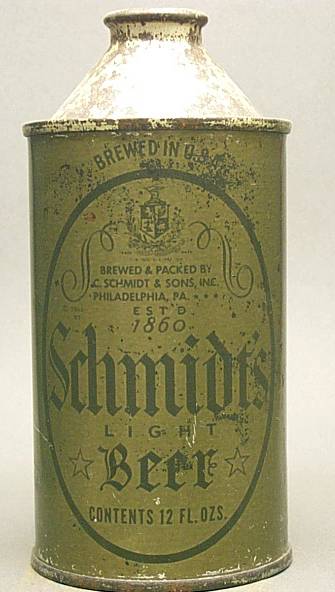

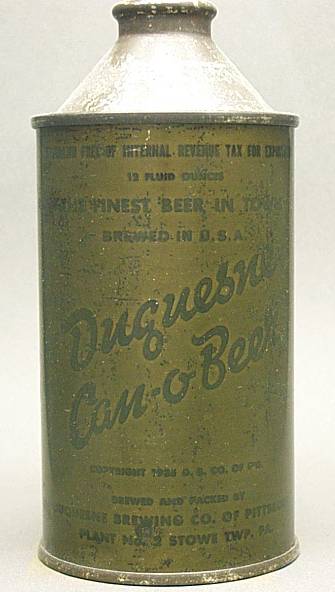

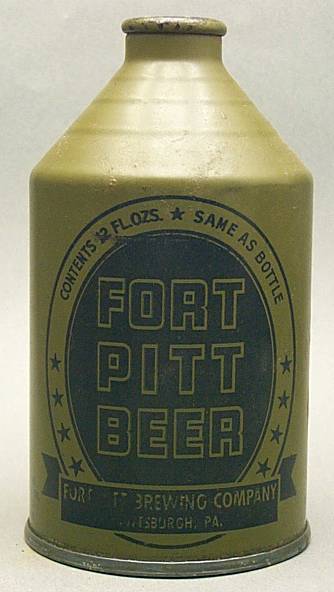

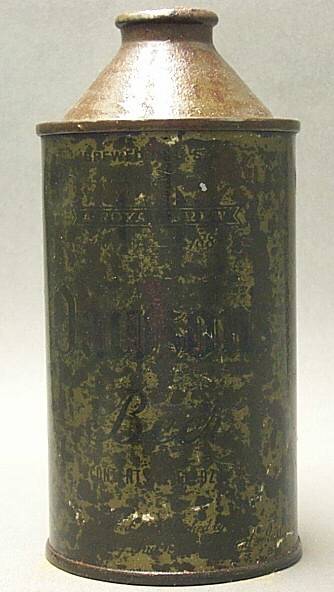

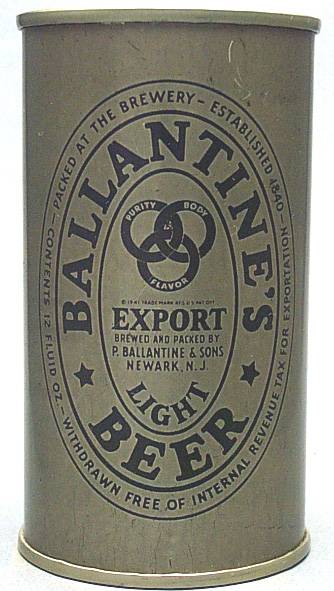

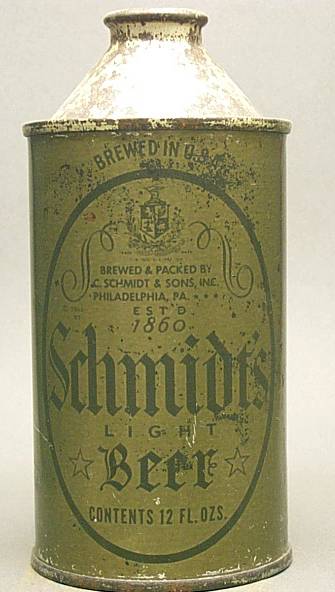

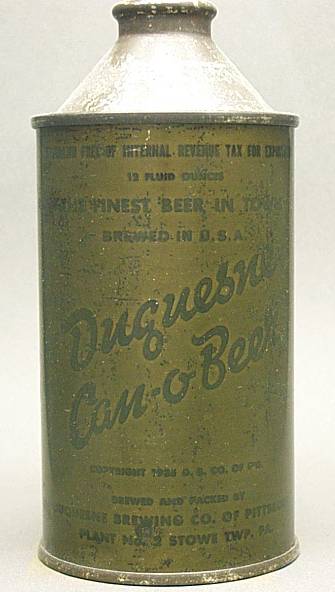

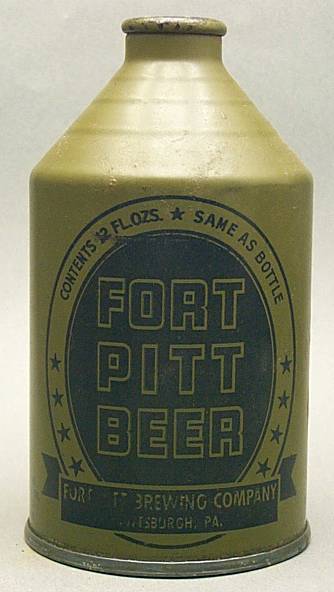

Canning stopped for World War II except for these Olive Drab "Camouflage" cans

sent to servicemen overseas.

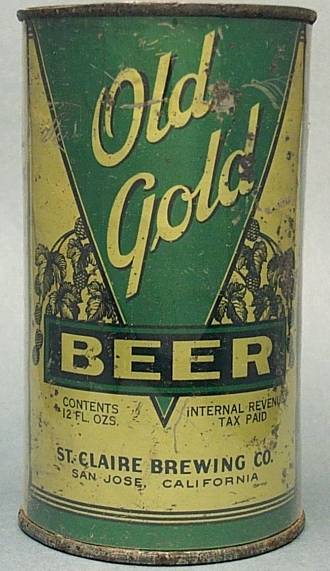

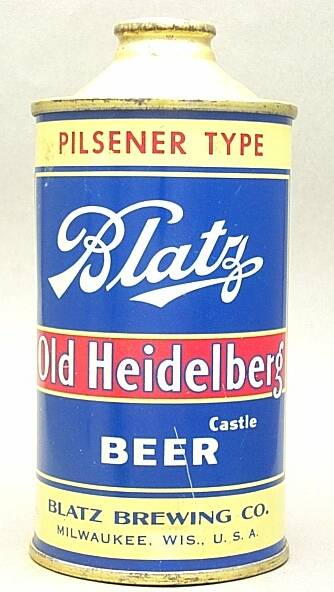

The entire beer can movement was completely derailed by World War II. Metal was directed

towards the war effort forcing brewers to package their beer almost entirely in

bottles. The exception to this was beer packaged especially for the overseas troops.

These beer cans were specially labelled "Withdrawn Free for Export". The word "free" refers

to being free from federal taxes. Prior to 1948, all bottled and canned beer had to

be clearly labelled "Internal Revenue Tax Paid".

A quick glance at all beer cans and

bottle labels of this era will reveal this mandated phrase. The insignia provides collectors

with a valuable tool in which to date old beer cans.

Many of the cans exported overseas for

the war effort were painted in the army's traditional Olive Drab color. Even the cans

tops and bottoms were painted this color to avoid reflecting light at night and

possibly giving an easy target for the enemy. These cans are especially difficult

to find in their home country today. More often than not they are found over in Europe

where they were shipped during the war. Cans shipped to tropical countries in the

Pacific often rusted away due to elements. There are likely some excellent camouflage cans

in the North African desert waiting to be pulled out of the sand. There are also

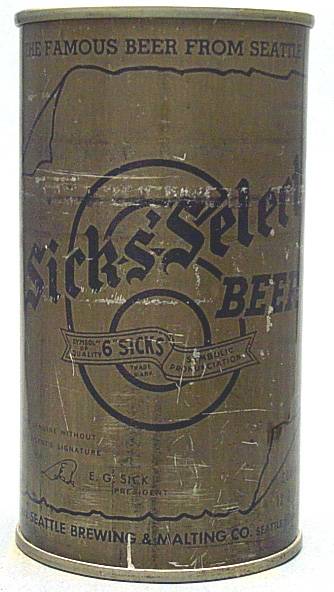

a large number of land mines out there as well. The camouflage cans pictured above

include the Ballantines from Newark, New Jersey and the Sicks Select from Seattle.

Also shown is the Duquesne cone from Pittsburgh, and the Fort Pitt crowntainer also from

Pittsburgh. Lastly, there a rare Dawson's cone from Massachusetts. The designs of each of these cans resemble the prewar designs offered

back home.

Home